We can develop new varieties of plants by crossing existing varieties and selecting the offspring based on the desired qualities. These qualities may include a higher yield or more intense flavour, a shorter flowering period or better resistance to diseases. Selecting the desired qualities is not only time consuming, but it often has other disadvantages.

As a new quality is ‘introduced’, qualities the plant already had may disappear. For example: a new variety has a very special flavour, but is more sensitive to mildew. If one of these varieties becomes infected with mildew, it's highly likely that it will produce less fruit and that the fruit it does yield will not taste as good as expected. And that is a waste. Nevertheless you can protect these plants without having to spray them.

The advent of monoculture

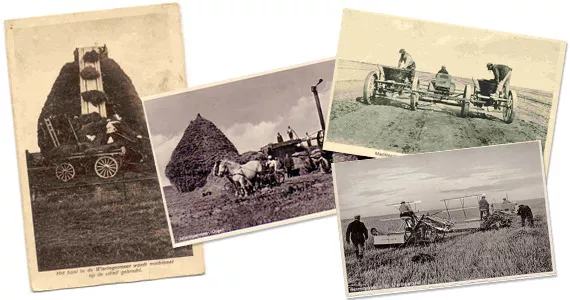

About 200 years ago agriculture in Europe underwent sweeping changes. This period is referred to as the agricultural revolution. At this time artificial fertilisers, cultivation machinery and new varieties were introduced.

A new system of cultivation was applied to support these interventions. These days this is practically the only agricultural system that most people know about. And most home cultivators use this system too: monoculture cultivation. In a monoculture only one variety at a time is cultivated in a limited space indoors or outdoor area.

And often in indoor cultivation an extreme form of monoculture is applied. This is the case if all the plants are cuttings from the same parent plant: therefore in genetic terms you are growing a single plant. However, monoculture does have its plus points. One advantage is that all the plants react in the same way to the nutrients and lighting conditions and that all the plants are similar.

The sombre side of monoculture

Unfortunately monoculture also has a downside. A monoculture can yield excellent results under ideal conditions, but conditions are not always ideal. One of the biggest disadvantages of monoculture is and will always be the increased loss of yield due to diseases and pests. This is because diseases can spread quickly through a crop if all the plants are (equally) susceptible. If the problems are not recognised on time or if action is not taken quickly enough, all the plants will become damaged. In fact the ideal solution to this problem is simple: cultivate a variety that is not susceptible to the pest or disease. Still there are situations in which such a solution is not feasible, for example:

- There isn’t a variety (sufficiently) resistant to the disease or pest plaguing the grower.

- The grower is faced with more than one disease or plague, but there is no variety that is resistant to this combination.

- The resistant variety has qualities that the grower does not want.

- The pesticides are not sufficiently effective to counter the disease or plague.

- It is not possible to use pesticides, for example in organic cultivation.

To find a potential solution to the last four situations cited above we will return to the situation prior to the advent of monoculture. For the first situation mentioned hygiene measures and (preventive) spraying may offer a satisfactory solution.

Different cultivation

Before the age of monoculture different crops were grown in between each other. And incidentally, this system is being reintroduced in many countries to keep plagues and diseases at bay. In China, for instance, wheat is grown on a large scale between rows of cotton plants to counter damage from insects. Growing different crops in between each other is also known as mixed cultivation.

This sounds good, but is a grower really prepared for all the extra work of growing sweet peppers in between the lettuce? But there are other methods. There is another type of mixed cultivation, known as mixed variety cultivation. As you can guess, in this cultivation form different varieties of a crop are grown together. This is done on a large scale in the United States with grain. But mixed varieties are closer to home than you think.

Whether it's for a football pitch or for your garden lawn, grass is always a mixture of varieties. A mixture of varieties gives you the advantages of monoculture combined with the advantages of mixed cultivation, as long as you select the right combination of varieties.

Why mixing works

In this section we will examine one of the main advantages of mixed variety cultivation: that is to suppress disease. The principle of this method of suppressing disease is based on the fact that the varieties have differing susceptibility to disease. We can illustrate this with the following example. Two varieties are grown together and planted alternately. One of the two varieties is fully resistant to mildew, but the other variety is very sensitive.

As we can see in the figure, this mixture of plants suppresses the spread of disease in two ways as follows:

- Plants of the susceptible variety are further apart from each other (thinning effect). A mildew spore that falls from an infected leaf will not reach another susceptible plant.

- The non-susceptible plants of the resistant variety form a barrier between the susceptible plants. A mildew spore that in a monoculture would fall far enough from the infected leaf to land on another susceptible plant, will now land on a resistant plant.

Unfortunately, in practice the varieties are not fully resistant to a disease. But luckily, to perform in a mixture a variety does not have to be fully resistant. The principle relies on delaying the spread. The greater a plants resistance the greater the delay in spreading the disease.

In the susceptible plants mildew spores from the sick plant infect neighbouring plants, which in turn infect their neighbouring plants.

The thinning effect. Because the susceptible plants are further apart and are mixed among resistant plants, it is more difficult for spores from the sick plants to reach the other susceptible plants.

The barrier effect. Because non-susceptible plants are planted between the susceptible ones, these act as a barrier, most of the mildew spores cannot pass.

Misunderstandings about mixtures

People often think that in mixed cultivation with two varieties the occurrence of disease is halved, but this is a misconception. The degree of infection is the square of the disease spread. In other words if you reduce the spread of the disease by half, the degree of infection is reduced by the square of the half. Just suppose that 64% of your plants are infected in a susceptible monoculture. That is 82. In a mixture with a non-susceptible variety this would then be the square of half of eight, therefore 42. That is 16%.

Another frequently voiced reason not to mix varieties is that people think it will reduce the size of the crop. Still the average harvest from two monocultures is almost always lower than the harvest from a one to one mixture with the same two varieties. In addition, there is less pressure on the plants due to diseases and other factors play role too, such as more efficient use of light.

Even though you can grow less of your favourite, but susceptible variety in a mixture, the yield per plant may be considerably higher. The fact remains that you shouldn't start experimenting with a mixture if you think you can get a better yield from a monoculture.

Disadvantages of mixed variety culture

You shouldn't cultivate susceptible varieties in a mixture. This is absolutely pointless. Select the most resistant variety and grow this in monoculture. When Dutch farmers started mixing varieties of wheat towards the end of the 1970s to counter attacks of rust they were thoroughly unsuccessful, simply because there were no resistant varieties. You mix crops so that you can cultivate a susceptible variety because it has important characteristics. When selecting varieties to mix you will have to consider the height of the plants. Varieties that differ greatly in length cannot be easily mixed, because the taller variety will take light away from the variety. Varieties that grow to more or less the same height can be easily grown in between each other. They will usually grow to an average height.

Another aspect that you should consider is that mixing the plants to delay the spread of disease is only effective if there are sufficient plants in the mixture. So a good argument against mixing is that in a growing area there are insufficient plants anyway. Yet, as a home grower, you could benefit from a mixture, even if it is only because your plants are often very close together. Remember that a mixture will only delay the spread of disease.

If in a monoculture situation disease will considerably reduce the volume of the crop then it is certainly worth considering mixed cultivation. Of course, you shouldn't walk between the plants as this will only help spread the disease throughout the crop. If you really need to walk between the plants, then leave enough space for a path when planting out.

If the infection in a crop is homogeneous and/or heavy, there will be little to no benefit from mixed cultivation.

Putting theory into practice

If you want to put together a mixture of varieties yourself, you will soon discover that, generally speaking, little is known about the resistance of the different varieties. And if a resistance is indicated, no degree of resistance will be stated. Unfortunately, this doesn't make it easy to create a good mixture. The sparse availability of resistant varieties almost creates the impression that growers are not troubled by disease.

Once you have found a variety that is sufficiently resistant, there are different ways of mixing it. If you grow from seed, you can mix the seed in advance of sowing, for example in a cement mixer or you can plant the varieties in alternate rows. You can even mix more than two varieties. If you are growing from cuttings, you can arrange the plants in different patterns. Good alternatives are fully mixed or in rows at right angles to your ventilation source. Remember that there is no point in planting a mixture if you are going to walk between the plants. In that case you will be the one spreading disease among your plants!

Returning to the problems we mentioned earlier:

The problem of more than one disease or plague, but that no single variety is resistant to that combination of diseases or plagues. One possible solution would be to mix a variety that is resistant to Botrytis (bud rot) with a variety that is resistant to mildew.

In the event the resistant variety doesn't have the particular properties you want to grow, you could consider growing your favourite variety with a great flavour but that is very sensitive to spider mite along side a variety that is resistant.

Even though growing a mixture of varieties can offer solace in certain situations, prevention is always better than cure. Then you can plant your favourite variety in monoculture and enjoy the fruits of your labour to the full.